Tradução e análise de palavras por inteligência artificial ChatGPT

Nesta página você pode obter uma análise detalhada de uma palavra ou frase, produzida usando a melhor tecnologia de inteligência artificial até o momento:

- como a palavra é usada

- frequência de uso

- é usado com mais frequência na fala oral ou escrita

- opções de tradução de palavras

- exemplos de uso (várias frases com tradução)

- etimologia

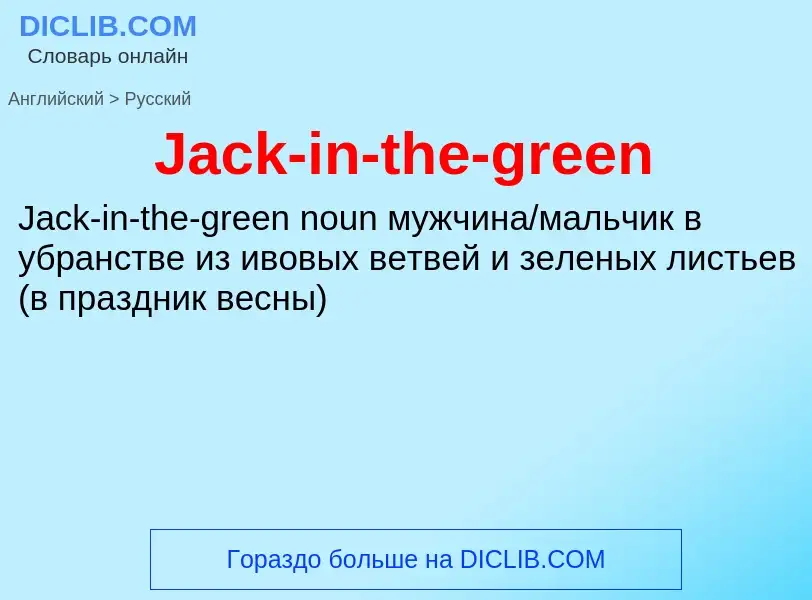

Jack-in-the-green - tradução para Inglês

[dʒæk|inðə'gri:n]

существительное

общая лексика

(Jack-in-the-green) мужчина или мальчик в убранстве из ивовых ветвей и зелёных листьев (в праздник весны)

разговорное выражение

английская примула

существительное

общая лексика

мужчина/мальчик в убранстве из ивовых ветвей и зеленых листьев (в праздник весны)

Definição

Wikipédia

Jack in the Green, also known as Jack o' the Green, is an English folk custom associated with the celebration of May Day. It involves a pyramidal or conical wicker or wooden framework that is decorated with foliage being worn by a person as part of a procession, often accompanied by musicians.

The Jack in the Green tradition developed in England during the eighteenth century. It emerged from an older May Day tradition—first recorded in the seventeenth century—in which milkmaids carried milk pails that had been decorated with flowers and other objects as part of a procession. Increasingly, the decorated milk pails were replaced with decorated pyramids of objects worn on the head, and by the latter half of the eighteenth century the tradition had been adopted by other professional groups, such as bunters and chimney sweeps. The earliest known account of a Jack in the Green came from a description of a London May Day procession in 1770. By the nineteenth century, the Jack in the Green tradition was largely associated with chimney sweeps.

The tradition died out in the early twentieth century. Later that century, various revivalist groups emerged, continuing the practice of Jack in the Green May Day processions in various parts of England. The Jack in the Green has also been incorporated into various modern Pagan parades and activities.

The Jack in the Green tradition has attracted the interest of folklorists and historians since the early twentieth century. Lady Raglan – following an interpretive framework influenced by James Frazer and Margaret Murray – suggested that it was a survival of a pre-Christian fertility ritual. Although this became the standard interpretation in the mid-twentieth century, it was rejected by folklorists and historians following the 1979 publication of Roy Judge's study on the custom, which outlined its historical development in the eighteenth century.

![bogey]] at Jack in the Green, Hastings. bogey]] at Jack in the Green, Hastings.](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Special:FilePath/Jackinthegreen.jpg?width=200)